by Elizabeth Marquart

It’s still pitch dark. Relieved, I hear the first cock’s crow in the village. A choir of cocks complete with each other as half an hour later, the sun rises: at six o’clock in the morning the day began at the equator.

Four hours earlier, Norah, the young woman from the house beyond the banana garden, died. My hosts are already aware of it, since their dog has been barking continuously to the visitor hurrying up to the mourning house. There, women gather in the dark room inside, while men light a big fire outside. People are scared to be alone in the presence of the dead body. During these hours, fears and mourning needs to be shared. As the burial shall be this very day, the neighbors must have dug the grave and bought a coffin. Those who have money can contribute some. As all of them are poor and have no relatives left, this funeral will be very soon. In early times, this was different. Traditionally, the burial rites were carried out after three days for a woman and four days for a man. All relatives then went into bush, shaved off their hair and got water for cleaning themselves from a water hole which was not allowed to be used as a source of drinking water. They made a feast in which they ate, drunk, sang and danced. Nowadays, they stopped this because of too many deaths. The village people can no longer manage old traditions beside their daily work. The AIDS epidemic is causing too big gaps. Fortunately, Norah has died here in the village and not in the town. The transport of the body to her father’s place would have cost too much money.

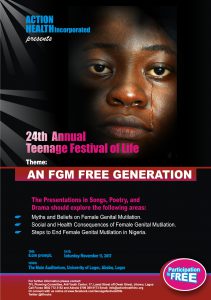

Young Women are at Highest Risk

The WHO (World Health Organization) estimates that in Sub-Saharan Africa about ten million adults have been infected, five million of them are women. They gave birth to one million children infected with HIV by intrauterine or perinatal transmission as well as via breast milk. Initially, HIV spread in cities, then along highways to rural areas. Poverty and drift from country to town broke the family ties. Widely spread sexually transmitted diseases, which usually go untreated, favor the spread of HIV. Young women, between 15 and 24 years old, are at high risk. Their partners often are older, experienced men with many sexual relations and a greater risk of getting infected. In Africa, more than 90% of all HIV infections are caused by heterosexual transmission. Women are brought up to be subordinate to men. Many cannot live a determined sexual life. They are intimidated by men and are not free to resist their institutional power structure.

All social sectors show the disadvantages of girls and women: education, health services, commerce and property rights. Whether this is the fact because of tradition or through “civilization” and Christianity, I cannot decide. As a European, I should not judge the African tradition. But what I notice is the obvious impact of the epidemic on women! They permanently have to face the consequences of economic problems and concerns for the children, who often remain stigmatized and as uneducated orphans. Many programmes for AIDS prevention are proclaimed and carried out to reduce HIV infection. But anti-AIDS campaigns are remarkably often of patriarchal logic! Men and women’s behaviors are not considered as two different gender-related patterns. Most campaigns strategies are two-faced, are even of double-standard morals.

Power and Morals

Let me illustrate this: An anti-AIDS activity first presents facts. Adults, youth or street children listen to the technical explanations-whether they understand them or not. Ways of infection and risky habits are described. Those campaigns assume that present usual sexual practices are stupid and irrational; otherwise there wouldn’t be so many infections. “Rational sexuality” is called upon and the therefore necessary “sexual behavior change” is proclaimed. Slogans like “a, b, c” (for abstinence, be faithful, condom) are used in Kenya to promote rational and controlled sexual behavior.in Uganda, the children between five to fifteen years are looked upon as the “window of hope” and educated to avoid “risky behavior”. The church and the national groups recommend as the most effective prevention of HIV infection a “behavior change” for sexuality active people, which means, like in Kenya, abstinence for the youth, faithfulness for couples, and in “special cases”, condoms. The Uganda AIDS Commission advises: condom promotion is undertaken using a quiet and responsible approach”. Appeals are generalized so as not to snub political and church leaders. Gender-related differences are not tackled. Promiscuity of men is not addressed; it’s either ignored or treated leniently. Reality and actual power structures are veiled. A married woman, for example, who knows about her husband’s girlfriend or even his infection, whose husband show insensitivity, doesn’t dare to refuse his sexual demands because of fear of being beaten and losing respect in the family.

Norah: A Typical Fate

Norah, the young deceased, grew up in the village. Her father left the family to look for a job, but he never showed up again. The mother moved to town with her children and opened a beer-kiosk. Norah noticed her mother’s health problems some time later. When the mother got severely sick, they returned home to their village. Neighbors visited them, and, to comfort them, said the fever would soon be over soon. When the mother was told in the hospital that nothing could be done for her, she sent for the traditional healer and ate all the earth balls (mumbwa). At that time, Norah was twelve years old. She helped her mother whenever she could. She brewed the local beer and sold it, care for the little sister and washed her mother when she suffered from diarrhea. Although people watched the mother surreptitiously and whispered “slim” or “the disease”, Norah was somewhat glad she could get school fees to be able to finish her “primary seven”. She also helped her mother by reading and filling out papers. The disease dragged on for three years, and sometimes it seemed as if her mother was getting better. But when she got pneumonia, they quickly returned home again, where she died and was buried in her father’s backyard. After some time, Norah couldn’t grow enough food for her and her sisters, and when she was 16 years old, they went back to the town where she continued the beer-kiosk. Even school fees for the little ones she would afford through her work, and sometimes she got gifts from her friends. Village people liked her because of her fine work and competence. She even was admired by the teenagers because she seemed to be able to combine the responsibility of a rural woman with the self-reliance of an urban woman. That’s why she was always visited by her neighbors when she had to return home because of her poor health. When a volunteer village-counsellor advised her to go for HIV antibodies test, she knew that she would have the same disease as her mother. From then on, she took care of herself and followed the instruction of the counsellor, ate plenty fruits and vegetables, didn’t work too late in the evening and boiled her drinking water. She also made her boyfriend use condoms, if they were available. She mostly worried about the future of her sisters and talked it over with the counsellor. Norah died unexpectedly, but not suddenly, at the age of 21.

Culled from ONE Strong Voice: Writings on Women and AIDS, UNAIDS, July 1996.

You must be logged in to post a comment.